Continued from Part 1.

ONE OF ANCHORAGE'S WILD SIDES

Anchorage's slogan is Big. Wild. Life. This is one of its crown jewels.

The first place we stopped this morning on our day trip along the

northern edge of Turnagain Arm was Potter Marsh, a bird refuge and

nesting area right next to the Seward Hwy. south of Anchorage.

Extensive boardwalks and decks allow visitors to get close to the

waterfowl and mammals who call the 564-acre marsh their home or visit it

during migration:

The refuge was established in 1971 to protect fish, birds, and other wildlife

and their habitat, while providing humans with recreational opportunities.

It is one of over

thirty wildlife refuges, sanctuaries, and important habitat areas

managed by the Alaska Department of Fish & Game. We plan to visit

more of them while we're in the state.

Our tourist information books and pamphlets only briefly

describe the Anchorage Coastal Wildlife Refuge, more commonly called

just "Potter Marsh." Most

of the information I'm relating here is from numerous interpretive

panels at the entrance (below) and along the boardwalk:

Note: there is

no fee to park or visit any part of the refuge, which is great. This natural haven

provides some of the best free entertainment, enjoyment, and education

in Alaska. We loved it.

Second note:

dogs aren't allowed on the boardwalk over the marsh -- especially

"duck dogs!" (Ha. Cody-the-Labrador-retriever doesn't even know what a

duck is.) Some hunting is allowed in other parts of the refuge at

certain times but not in Potter Marsh.

Because of its

proximity to Anchorage, the number of birds and other critters it attracts from spring

through fall, the general beauty and quiet, and its extensive system of boardwalks that are accessible

to everyone (walking or in wheelchairs), Potter Marsh is one of the most heavily-visited wildlife

sites in the state.

We arrived about 10

AM this breezy, cloudy morning and the parking area was about one-quarter full.

Some of my pictures have people in them but the boardwalks and trails

were not crowded.

We managed to avoid

most of the people by going the other direction or pausing at places

along the boardwalk where they weren't gathered.

From the entrance you

can go in two different directions -- to the south on a long "L"

toward the highway, where much of the open wetland lies, or north toward

the wooded area at the base of the Chugach Range:

The boardwalk twists

and turns in either direction. It's about a one-mile walk if you go out

and back on both legs.

There are numerous benches, decks extending over

the water, spotting scopes, and decorative touches, like the bird motifs

in the picture directly above.

A SERENDIPITOUS BEGINNING

Potter Marsh is a true rarity because of the way it came into existence.

Although people now realize the benefits of both creating and preserving

wetlands in their communities, they didn't know that early in the 20th

Century.

If it wasn't for the Alaska Railroad this wildlife refuge wouldn't exist

-- or wouldn't have existed until the Seward Hwy. was built in

later years. It was accidentally created in 1916-17 during construction

of the rail line from Seward to Fairbanks along the north side of Turnagain Arm.

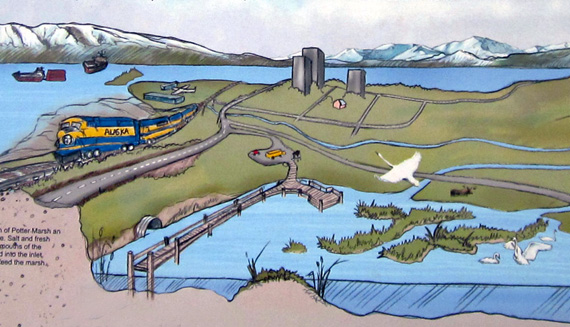

What is now Potter

Marsh lies between the base of the Chugach Mountains and Turnagain Arm,

as depicted in the graphic on the panel above (the mountains are off to

the right).

When the railroad was

being built workers created an embankment for the track. That embankment impounded several creeks and limited tides and storm

surges. What was previously mostly salt water in the original tidal

estuary at this location eventually became mostly

fresh water in the new marsh born behind the embankment.

One of the creeks flowing through the marsh

reflects mountains and clouds.

Low areas soon filled with creek water and became freshwater ponds. Marsh

vegetation grew. Both the water and plants attracted migrating waterfowl

and shorebirds, nesting birds, and mammals.

Because over time this marsh fills in with sediment coming down the

mountain streams, human intervention (i.e., dredging) is sometimes necessary

to maintain the water in the wetland. One of the interpretive panels describes

the process of "succession" in which natural environments gradually

change over time. This area is a good example of that phenomenon.

MARSH COCKTAIL

Potter Marsh is now predominantly a freshwater marsh sustained by rainfall,

snowfall, and several creeks flowing down from the Chugach Mountains.

However, the northwestern part of the marsh supports different plants

and animals than the rest of the marsh.

Under new and full moons, when the tides are especially high (and bore

tides are more likely to occur), salt water from Turnagain Arm flows

into the marsh and mixes with the fresh water, forming a brackish, salty

"cocktail."

Only salt-tolerant plants and animals can survive in that part of the marsh.

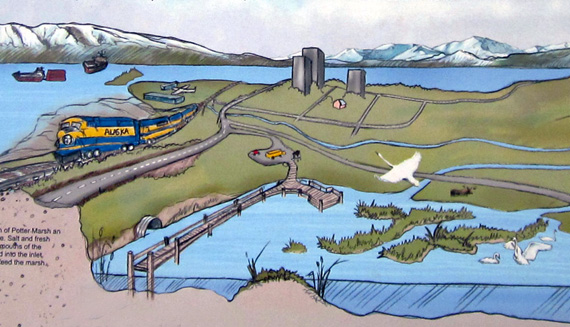

Humans have also had a hand in maintaining/preserving the habitat in

this area by constructing culverts under the railroad tracks and Seward

Highway, which also runs along the southern edge of the marsh, to

provide an avenue for the fresh and saltwater to mix like it used

to before the embankment changed the dynamics:

Without the culverts salmon wouldn't be able to return to spawn and

raise their babies, salt-loving plants wouldn't exist, food sources for

brown bears, eagles, waterfowl, and many other animals would be absent,

and Potter Marsh would overflow.

FEATHERED FRIENDS

This morning we saw all kinds of birds flying and nesting in the marsh.

We aren't serious birders so we don't know the names of most of them but

we still enjoyed watching them.

Some species live in the area all year long. Others are temporary

visitors.

Every year millions of birds migrate to and from Alaska from thousands

of miles away. Potter Marsh provides many of these avian ultra-travelers

the habitat they need either in transit to places farther beyond or for a

suitable breeding area all summer long.

At the entrance to the boardwalk we noted a hand-written dry erase board with the

birds and mammals people have spotted this week.

It was a long list including many that I've heard of (moose, muskrats,

bald eagles, mallards, Arctic terns, Canada geese, sandhill cranes,

ravens, sparrows, swallows, flycatchers, gulls, magpies, juncos,

pintails, teals, gulls, and robins) and some birds that are new to me

-- greater and lesser yellowlegs (medium to large shorebirds),

gadwalls (a kind of duck), and long-billed dowitchers (medium-sized

shorebirds). I had to look those three up.

Several of the interpretive panels describe the birds that live here all

year, only breed here in the summer, or just pause a while during

migration to and from other areas.

Two geese and a gosling, which is barely

discernable in the foreground

An example of a species that visits the marsh only temporarily during

migration is the trumpeter swan.

Alaska attracts about 80% of the world's population of trumpeter swans.

They winter along the coast of the Pacific Northwest and summer in

Alaska, enjoying the abundance of sunlight and natural resources. Many

swans visit Potter Marsh in the spring and fall on their way to and from

their breeding grounds farther north in the Arctic.

Trumpeter swans can be seen in this area in April-May and

August-September.

Although we missed that window of time here in Anchorage, we did see

some swans farther north in the Yukon and Alaska earlier in the month.

They built their nests on little islands of dirt and grass in the middle

of ponds to keep the babies safe from predators.

These two geese are harder to see in the tall

grass;

there are probably one or more goslings nearby,

too.

One of the migratory

species that may spend the entire summer at Potter Marsh is the Arctic

tern.

Arctic terns are

probably the ultimate "ultra-distance" migratory birds, flying more

miles each year than hummingbirds. They migrate over 22,000 miles each

year from Antarctica in the southern hemisphere's summer to the Arctic

in the northern hemisphere's summer -- and back again.

They especially like

the fish at Potter Marsh. The best time to see Arctic terns is mid-May to

mid-July. We saw some of them but I didn't get any pictures of them.

With my decidedly low-range digital compact Canon camera

I got some decent photos of a pair of geese close to the boardwalk near

the highway. Their four chicks were little balls of yellow fuzz.

As we walked outbound the chicks were close to one of the parents (in the brown grass

below):

When we came back a few minutes later all four were sheltered under one

of mama's large wings Ė very sweet (and cozy warm):

Other interpretive

panels describe the insects, amphibians, and mammals that inhabit this

ecosystem.

One of the more

interesting panels was about the life cycle of wood frogs, which

live in the marsh year-round. They survive the winter beneath the water

by going into a state of suspended animation by producing their own

"antifreeze."

Their bodies replace

the water inside their cells with a syrupy glucose mixture that prevents

dehydration and collapse of the cells while the frogs are hibernating.

The water between the cells freezes, then thaws in the spring

when the temperature warms up. The frogs hop out and breed, enjoying a

rather brief summer of activity before the temperatures drop and they

become frogsicles again.

That's a pretty neat Darwinian adaptation, eh?

We weren't able to

see any bears, moose, coyotes, fox, lynx, or even smaller critters like

rabbits on the boardwalk near the forest (photo above) but the views

from back there were so good I

didnít mind:

NATURE NEARBY

You don't have to be

a serious birder to enjoy Potter Marsh. It has something to offer almost

any nature-lover who takes the time to visit.

For starters, it's a

nature photographer's dream -- mountains, water, sky, and

interesting plant and

animal life all around:

This is a good place to have

strong binoculars or long camera lenses.

In the summer it offers residents and visitors

easy access to all kinds of wildlife and natural habitat, enhancing the

quality of life. It is an outdoor educational area for people of all

ages. When the salmon are running you can observe coho, king, chum,

sockeye, and pink salmon right from the boardwalk.

And despite the

nearby highway, it's a relaxing place to get some fresh air, sunshine,

and a little exercise:

Above and below: a long leg

of the boardwalk parallels pretty close to the Seward Hwy. It

wasn't too

distracting because we were

usually looking the other direction toward the marsh, searching for

birds.

Just bring a camera

and binoculars, a sense of wonder at the natural beauty around you

(mountains, forests, wetlands, ocean), and enjoy a quiet walk out and

back on the two long legs of the boardwalk.

And if you happen to be in Alaska during the winter, frozen ponds in

the marsh allow for ice skating, games of hockey, and cross-country

skiing.

The photography should be pretty "cool" then, too.

ULTRA WILDLIFE TRAIL

If you are a serious birder/nature lover, consider following all or

part of the Kenai Peninsula Wildlife Viewing Trail, which includes 65

sites that Alaska residents deem the best places to view wildlife.

This

collection of sites includes venues that range from easily-accessible roadside platforms to

remote backcountry hikes. You can get a guidebook for the wildlife trail at visitor centers and

bookstores in Anchorage or the Kenai Peninsula.

Fireweeds are just opening up

along a dirt trail near the parking area.

I assume there are similar wildlife trails in other parts of the

state, too.

It's possible to spot wildlife almost anywhere in Alaska, even

busy highways. We've seen all sorts of birds and mammals from the road

as we're traveling.

And I've already mentioned how many bears and moose roam around the city

of Anchorage!

Just keep your eyes and ears

open while riding, hiking, or running.

Next entry: our Byron Glacier hike and a visit to

the Begich, Boggs National Forest Service Visitor Center at Portage Lake

(complete with icebergs!)

Happy trails,

Sue

"Runtrails & Company" - Sue Norwood, Jim O'Neil,

and Cody the ultra Lab

Previous

Next

© 2012 Sue Norwood and Jim O'Neil