The Battle for Fort Pulaski during the Civil War marked a turning point

in military history and signaled the end of masonry fortifications. This

fort, named for a Polish war hero, has an interesting history.

I mentioned Count (later, General) Casimir Pulaski in a previous

entry about the old public squares in Savannah. In addition to

this fort, there is also an impressive statue of Pulaski in the

square named after him.

Pulaski lost his life in the successful defense

of Savannah during the American Revolution in 1779 and was honored

posthumously by grateful Georgians who appreciated all that he did for them.

Aerial view of the irregular pentagon shape of the

fort;

the entrance is

over the moat to the left. (Photo from the NPS

website)

Fort Pulaski was part of the coastal fortification system adopted by the

U.S. government after the War of 1812. It succeeded two previous forts

built at the same location. Although construction of this new fort began

in 1829, its armament and garrisons were still not complete at the

beginning of the Civil War. Despite that, its admirers considered it

invincible and "as strong as the Rocky Mountains."

Not. As it turned out, before U.S. (Federal/Union) forces could occupy the fort, they

had to conquer it from the Confederates and that included doing some

serious damage to the structure.

Georgia seceded from the Union in January, 1861. Before the state militia and Confederate

States of America could occupy the fort, they had to overcome the

stranglehold the U.S. Navy had on all the southern ports. They managed

part of that OK but made soon made a serious tactical error.

Gunmounts on the upper level of the southeast side of the fort

Too sure of the strength of the incomplete fort and unaware of the

strength of new Federal (Union) armament, the Confederates abandoned

nearby Tybee Island at the mouth of the Savannah River. That unknowingly

gave their enemy the only site from which Fort Pulaski could be taken rather easily.

The Federals acted quickly and moved troops to Tybee to prepare for a

siege on the fort in April, 1862.

The Confederate troops weren't particularly worried because Tybee Island was

a mile away over water and marshland. At the time there weren't any known cannons that could

breach the distance. What the Confederates didn't know was that the

Union armament included ten new experimental rifled cannons whose projectiles

could -- and did -- effectively shatter the walls of the fort.

Oops.

Cutaway of the new cannon used by the Union troops

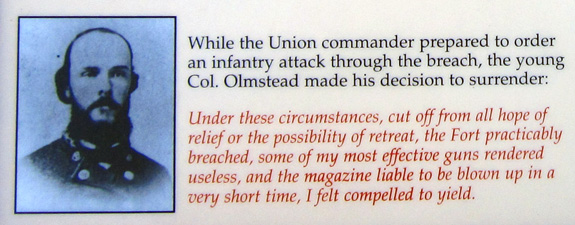

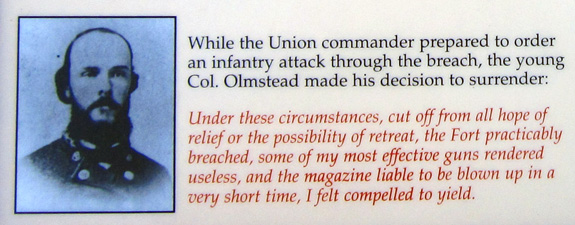

Impressed by the hopelessness of the situation and concerned about the

lives of his men, Commander Col. Charles Olmstead surrendered only 30

hours after the bombardment began.

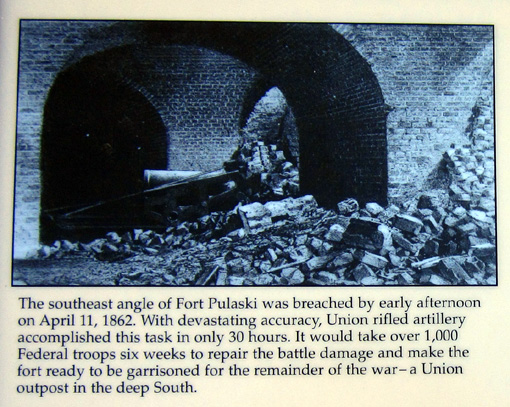

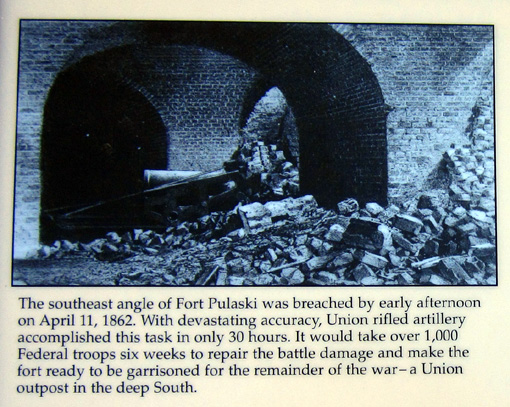

Above and below: photos and text from an

interpretive panel at the fort

Federal troops garrisoned Fort Pulaski until the end of the war and used

it to house Confederate prisoners.

The fort was unoccupied from the end of the Civil War until it became a

national monument in 1924 and was subsequently restored by the Civilian

Conservation Corps during the 1930s.

VISITING THE FORT

Last Friday

we drove to Fort Pulaski east of downtown Savannah, crossing several rivers to

reach McQueens and Cockspur Islands. Since the fort and surrounding property is

a national monument we got in free with our National Park Service senior passes.

Marina along the drive to Cockspur Island

We listened to a video about the history of the fort in the visitor

center first, then toured the exterior and interior of the fort on our own.

THE

DEMILUNE

There's a new word for you! We've toured several forts but haven't run

into that term before.

A paved path leads from the visitor center to the triangular patch of

land designed to protect the rear of the fort, which held the entrance,

from an invasion. Called the demilune, it was surrounded by a

seven-foot deep, 32-to 48-foot wide moat on all three sides:

During the Civil War the demilune was flat, with a

surrounding parapet. It held outbuildings and various storage sheds.

The large earthen mounds seen above and below were built after the war.

They cover four powder magazines and passageways to several gun

emplacements. It's literally and figuratively cool to walk through the

underground maze.

View looking down to the demilune from the upper

level of the fort

We crossed the moat on a small drawbridge to the demilune:

Chain that operates the small drawbridge

Above and below: under the mounds

DRAWBRIDGE & GROUND LEVEL OF THE FORT

The main drawbridge entry, positioned on the west (rear) wall, was designed

to be part of the fort's defense.

As the drawbridge is raised, a strong wooden grill drops through the

granite lintel overhead. Bolt-studded doors are closed behind that. An

inclined granite walk leads between two rows of rifle slits, past

another set of doors, and into the fort.

The wide moat also surrounds the five-sided fort.

The large grassy area inside the five-sided fort is called the "parade:"

The long west wall at the rear of the fort is called the "gorge wall."

It contains the sally port (fort entrance shown above), officers' quarters, and

other rooms.

Some of the rooms have been furnished as they were during the Civil War,

such as the commanding officer's quarters:

We made a clockwise circuit of the lower level, which is

characterized by thick walls and many structural arches:

While occupied by Confederate troops the northwest corner contained

40,000 pounds of gunpowder. The Union forces knew that and planned to

blow it up:

Even though the walls of this magazine were 12-15 feet thick, Col.

Olmstead knew that once the southwest wall was breached it would be

fairly easy for the Union army to blow up the magazine. To avoid carnage

to his men, he surrendered.

Continued on the next page . . .

Happy trails,

Sue

"Runtrails & Company" - Sue Norwood, Jim O'Neil,

Cody the ultra Lab, and Casey-pup

Previous

Next

© 2013 Sue Norwood and Jim O'Neil